Wi-Fi Hotspots Made of Homeless People: Not as Horrible as They Seem

South by Southwest now has its very own controversy. And it involves homeless people employed as, yes, wi-fi hotspots.

It seemed straight out of South by South Onion: the homeless people of Austin, being used as wi-fi hotspots for bandwidth-hungry, gadget-happy conference-goers. Wait, Homeless Hotspots? Wi-fi hotspots made out of homeless people? It's got to be a joke, right?

But, no. Homeless Hotspots is a very real -- and very earnest -- initiative, imported to Austin for this week's South by Southwest Interactive festival by BBH Labs, the skunkworks-y innovation unit of the marketing firm Bartle Bogle Hegarty. (You may remember them from such projects as the Axe Body Spray oeuvre, as well as The Guardian's recent Three Little Pigs ad.) BBH Labs has worked in the past on the problem of homelessness in New York City, through its Underheard in New York project; Homeless Hotspots, they say, is an attempt to bring a similar "charitable experiment" to Austin.

Participants in the program carry MiFi devices with 4G connectivity. "Introduce yourself," BBH explains, "then log on to their 4G network via your phone or tablet for a quick high-quality connection. You pay what you want (ideally via the PayPal link on the site so we can track finances), and whatever you give goes directly to the person that just sold you access."

The point of the project, says Saneel Radia, the head of innovation at BBH Labs, was not to objectify homeless people, or, more broadly, to treat human beings as tech infrastructure. On the contrary, he says: It's trying to empower them.

The project attempts to modernize the street-newspaper model employed to support homeless populations, Radia explains.

As digital media proliferates, these newspapers face increased pressure. Our hope is to create a modern version of this successful model, offering homeless individuals an opportunity to sell a digital service instead of a material commodity. SxSW Interactive attendees can pay what they like to access 4G networks carried by our homeless collaborators. This service is intended to deliver on the demand for better transit connectivity during the conference.

Again, though: Homeless. Hotspots. As Tim Carmody put it, "It sounds like something out of a darkly satirical science-fiction dystopia."

So: publicity stunt, right? And, yes, in part. "Certainly, our goal was to have people talking about this," Radia told me. But it was a well-intentioned publicity stunt, he says. If, for a week in March, a hefty percentage of the U.S. media operation is roaming the streets of Austin, cursing the irony that is a digital media conference with awful web connectivity ... why not take advantage of that fact to publicize a problem that is much, much bigger than choppy wi-fi? Web connectivity is, at SXSW, the area "where supply and demand are most discrepant," Radia notes; it seemed a logical place to make a point.

The question is how best to make that point. On the one hand, it's hard to argue against publicizing homelessness as an ongoing problem, and harder still to argue against publicizing that problem given the backdrop of the privilegefest that is South by Southwest. It's also hard to argue against an initiative that ends with homeless people -- 14 men and one woman who are part of the Case Management program at Austin's Front Steps shelter -- earning money in exchange for providing a service that, at the wi-fi-strapped conference, has a market value.

But it's also hard not to think, overall, "UGH." Not only does the whole thing reek of digital privilege and entitlement and seem to symbolize, in two neat little words, everything that is wrong with South by Southwest/the economy/the world, it also suggests the normalization of a new power dynamic: digital colonialism. There's the project's name, first of all, with its cheerful union of poverty and privilege. There's the fact that Homeless Hotspots' Human Hotspots are, on the project's site, plotted on an interactive map for the benefit of Austin's wi-fi-seekers, their avatars floating merrily upon streets and avenues like so many bars and barber shops. There's the fact that the Human Hotspots designate themselves as such by wearing t-shirts proclaiming their Human Hotspot status. (And "the shirt doesn't say, 'I have a 4G hotspot,'" ReadWriteWeb's Jon Mitchell points out. "It says, 'I am a 4G hotspot.'") The practicality of the initiative collides, violently, with the morality of it. As a New York Times reporter who encountered a Human Hotspot put it: "It is a neat idea on a practical level, but also a little dystopian. When the infrastructure fails us ... we turn human beings into infrastructure?"

To make an obvious point, though: The real failure of infrastructure here has actually very little to do with technology. It's easy to mock Homeless Hotspots; it's easy to disdain it; but, really, what would we prefer, the typical combination of ignoring and ignorance that we reserve for most of our dealings with the hundreds of thousands of people who are homeless in the U.S.? BBH is taking a bad situation -- the fact that Austin has people who lack homes and jobs and who, given the choice, would prefer to have both -- and trying to do something constructive with it. Yes, it's gimmicky; yes, it's weird; yes, it's initially kind of offensive. It's right that our gut reaction to Homeless Hotspots is disbelief and disgust; it's right that we're alarmed at the idea of turning people into platforms. It's also right, though, that we take the next step to ask ourselves: What's the alternative? That we go on ignoring homelessness? It's nice to be reminded that Austin, even in March, is about more than serendipity apps and rooftop pool parties.

It's worth noting, as well, that the indignation of the whole affair seems concentrated on the side of the privileged. Clarence, one of the hotspot managers, doesn't seem to feel that he's having his dignity stolen, one connection at a time. Nor does Gilbert. Nor does Stacia. The fifteen project participants (fifteen due simply to BBH budget constraints) were selected, Radia told me, through an application process -- a fairly intricate affair that involved formal applications and recommendations from the case managers at the Front Steps transition program, which works to find jobs and other opportunities for its clients. The Homeless Hotspot participants didn't merely volunteer to be part of the program; they worked for the opportunity. And it was an opportunity not just to make some money, but to tell their stories.

Here's Clarence:

And here's Jeff:

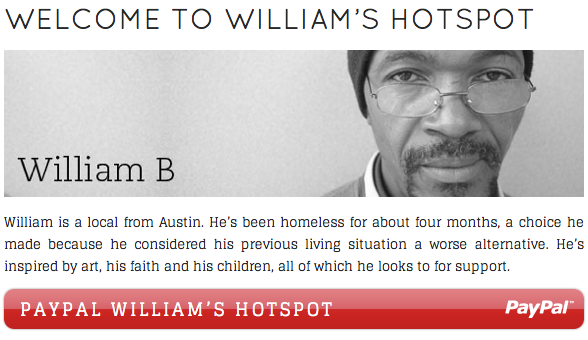

And here's William:

Radia stresses the entrepreneurial aspects of the hotspot system, the fact that, whatever their t-shirts say, Austin's wi-fi device operators are the "managers" of those devices and the customer experience that comes with them. Their earnings depend on their work and their charm. Though Radia is mum for the moment on how much money has been made so far (BBH Labs will release the data, he says, after SXSW has ended), he does note that the most gregarious of the project's participants are also the ones who tend to make the most money. Homeless Hotspots is a charity that is also a business.

Yes, there are ironies to it. Yes, there are hypocrisies to it. But they're ironies and hypocrisies that we should be talking about, rather than outrage-ing and indignation-ing and then moving on. We talk, triumphantly, about wearable technologies; we find it wacky and quirky when, say, FedEx pays a South by Southwest-goer to become a human device-charger. Why does the possession of a home mean the difference between empowerment and insult when it comes the adoption of these technologies? If we're appalled at the idea of Homeless Hotspots, great -- we should be. But perhaps we should be directing our indignation at "homeless" rather than "hotspot."

Update: Buzzfeed's Jon Hermann talks with Melvin, one of the Homeless Hotspots participants. Melvin says of the project: "It's all good." And the Wall Street Journal talks with Clarence Jones, who declares the project a success.

Image: YouTube.